Australia's Brexit Moment

The Voice referendum result wasn’t a defeat for Constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. It was a defeat for Australia's political class.

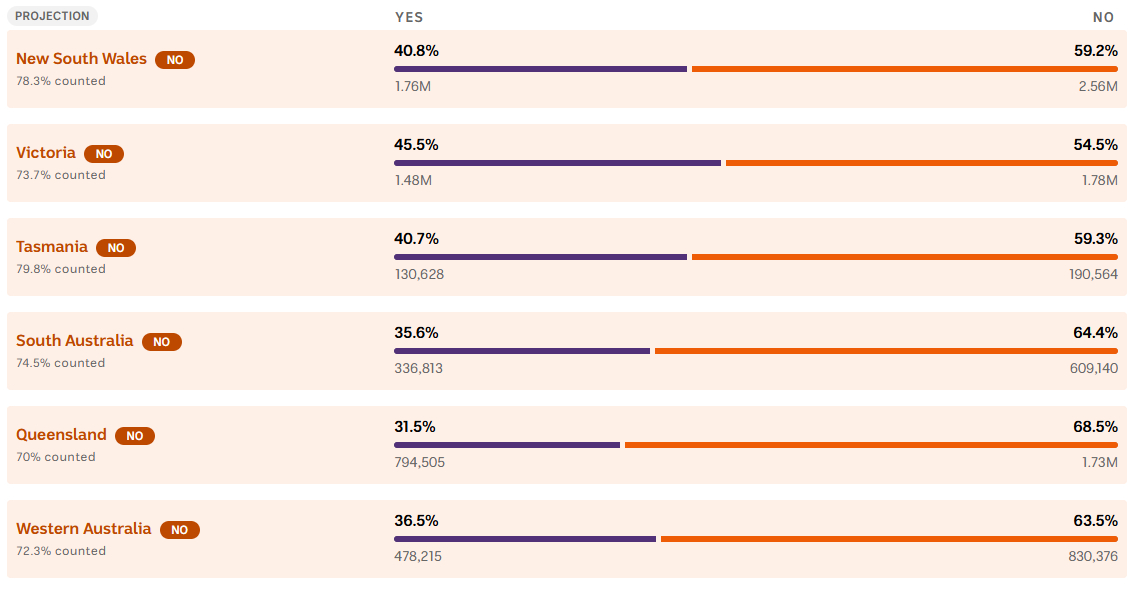

The Voice vote has failed: in the nation, in all six states, in the Northern Territory—everywhere except the ACT. The government-proposed, establishment-endorsed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to Parliament and Executive Government, which would have enshrined an indigenous advisory body in a new chapter of Australia’s Constitution, has been roundly defeated. It will not be revived.

The patterns of Australia’s Voice vote resemble nothing so much as those of Britain’s 2016 Brexit referendum. Just as with Brexit, a country’s cosmopolitan establishment and the institutions they administer demanded that the rest of the country embrace their highly cultivated but ironically parochial political preferences.

The Voice won inner Sydney but lost the rest of New South Wales. It won inner Melbourne but lost the rest of Victoria. It won Brisbane but lost Queensland, won Adelaide but lost South Australia, won Perth and Freemantle but lost Western Australia, won Hobart but lost Tasmania. The Yes campaign did not prevail in a single electorate outside the centres of Australia’s capital cities.

The key question for the future of Australian politics is thus: does anyone want to represent the majority of the country? In the wake of Saturday’s referendum results, the only clear answer to that question is “No”. Read my full analysis at Quadrant online:

For any democrat, a key shortcoming of the proposed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice was its lack of democracy. Unique among developed democracies, Australia’s Constitution empowers the contry’s Parliament to make laws with regard to “the people of any race for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws". This special “race power” has only ever been used to legislate with regard to indigenous people. It arguably calls for an indigenous voice to provide guidance and feedback.

But the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice was never intended to give Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians a Voice. It was designed to give Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander elites a voice. There were no provisions in the Voice amendment for indigenous democracy. Quite the contrary: the Indigenous Voice Co-design Process never even considered it. Again, you can find my article on this in Quadrant online:

Indigenous Australians deserved better. They deserved what indigenous peoples in the United States, Canada, Norway, Finland, and New Zealand all take for granted: a vote. Every other country that has formal representative mechanisms for indigenous peoples organises them on the basis of one person, one vote. Australia’s indigenous elite, supported by the country’s broader political class, seems afraid to let the country’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people vote for their own representatives. Maybe they’re afraid to know what indigenous Australians really want.

As long as Australia is going to make special policies for indigenous citizens, it should have some form of democratic consultative mechanism for those affected. For those who’d like to know more about how the Voice was intended to work in Australia, and how those mechanisms compare to institutions for indigenous representation in other countries, I’ve recorded a video lecture. You can find it on YouTube at:

Everyone who is active in Australian intellectual life desires meaningful progress for indigenous people. Everyone wants lower rates of incarceration and higher rates of employment for indigenous youth. Everyone wants to see more indigenous university graduates. Everyone wants to see reductions in domestic violence in indigenous communities. Everyone wants to close the gap in indigenous life expectancy. The only disagreement is on how to best accomplish these goals, not over the goals themselves.

Unfortunately, the highly-educated urban professionals who form the core of the Yes vote believe not only that their preferred solutions are the correct ones, but that theirs are the only moral ones. They openly disdain the opinions of those who live outside the urban cores of the capital cities, who lack advanced university degrees, or who are too world-wise (read: elderly) to be fooled by facile quick-fix policy rhetoric. The sense of absolute entitlement exhibited by the Yes campaign was palpable—and repulsive.

Democracy requires respect for the voters, and in the Voice referendum (as with Brexit) that respect was noticeably lacking, and lacking on one side only. The Yes side demanded that their schools, employers, and membership organizations publicly support their position; the No side only demanded only that they stay out of politics.

Now, those institutions must reckon with the fact that the clear majority of their stakeholders voted No. They are unlikely to have the maturity to acknowledge this. But if they double-down on the narrative that all opposition to the Voice was motivated by ignorance, ill-will, or outright racism, they will only reinforce their own anti-democratic credentials. A massive electoral defeat calls for self-reflection. Britain’s Remain camp scorned that opportunity in 2016. Australia’s Yes camp would do well to learn from their example.